“…The Greatest Crime Ever Committed in the Whole of History…”

“This is without doubt the greatest crime ever committed in the whole of history…” These words of anguish are recorded in the diary of Abraham Lewin, a Jewish intellectual and member of the Jewish underground Archives, on August 28, 1942 (Lewin 270). Lewin, confined to the particularly brutal Warsaw ghetto, provides insight into the daily life of the largest Jewish population under the control of the Third Reich. While resistance was dangerous, the Jews of Warsaw, whom Lewin viewed as “the most vibrant nerve of [their] people”, did not submit to the Nazis without a fight (Lewin 232). Instead, they initiated the first armed uprising against Germans in Nazi-occupied territory during World War II. While considered a military defeat, the Warsaw ghetto uprising paved the way for future uprisings, like the Warsaw Uprising, or General Uprising, of 1944, and served as an inspiration for future events of resistance (Tucker 164). Brave men and women also maintained an extensive underground archive chronicling German actions for posterity (Arens 1). In order to understand how and why these unprecedented acts of physical and intellectual resistance occurred and why they were successful even though the ghetto was ultimately destroyed, it is necessary to understand the conditions of the Warsaw Ghetto that led to their inception.

Historic Anti-Semitism and the New Nazi Policy

The history of Jews in Warsaw was one marked with tension; undercurrents of anti-Semitism did not begin just before World War II, but extended far into Poland’s past. The first record of Jews in Warsaw dates to the fifteenth century AD, when it was the capital city of what was then known as the Principality of Mazovia (Gutman, xiv). When this principality was annexed to the Christian Kingdom of Poland in 1527, Jews were forced out of Warsaw and into the neighboring suburb of Praga; Jewish residence in Warsaw was not again officially recognized until 1801 – 1802, when the Prussians occupied Poland during the period of the Three Partitions (Gutman, xiv). Jews began to assume important roles in the trade, industry, and banking sectors of Poland’s economy, and by 1816, the 15, 600 Jews in Warsaw made up 19.2 percent of its population (Gutman xiv). The economic success of these Jews provoked some feelings of resentment among Poles, and those sentiments were exacerbated later in the century by the influx of Russian Jews (and those from other Russian provinces, like Lithuania) after a series of pogroms, or organized attacks against Jews, in the early 1880s (Gutman xiv).

By 1931, there were approximately 352, 650 Jews in Warsaw; their relative economic success in the midst of a worldwide depression brought about anti-Jewish boycotts and heightened pressure for Jews to leave the country (Gutman xvii). Emigration proved difficult, however, because the countries which had been generally welcoming—especially the United States and the Palestinian territory controlled by the British—had imposed immigration restrictions (Gutman, xvii). Rather than having a window of opportunity to leave their country, Polish Jews were trapped, and as historian Israel Gutman notes, the “war descended on [them] like a thunderbolt, leaving no chance to escape” (Gutman xviii).

The Nazis invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and within a few days’ time had reached the gates of Warsaw (Gutman 3, 5). Bombardments and shelling were frequent, especially in the Jewish Northern Quarter on the religious holidays of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (Gutman 8). On September 28, 1939, the Nazi siege on Warsaw stopped, and the citizens of the capital emerged from hiding to discover that the raid had resulted in about fifty thousand casualties (Gutman 8). The Nazis waited for several days to enter the demolished city, and looting was rampant (Gutman 8). Upon their entrance, anti-Jewish policies were immediately enacted. Jews were kidnapped from the streets and assigned to forced labor, Jewish property and possessions were confiscated, and Jewish families were often denied food in German aid stations that served Poles (Gutman 8 – 9).

Life in the Ghetto

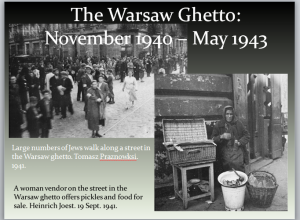

On November 16, 1940, German troops sealed the Wohnbezirk, or “Jewish residential district”, that they had created in Warsaw’s center after labeling Jews “unclean” following a typhus outbreak (Lewin 2). The forced relocation of 138,000 Jews from outer-lying districts into the “Jewish quarter” was the first of multiple relocations and evacuations to take place over the next few years; by March of 1941, its population had swelled to 445,000, and it became the site of the largest concentration of Jews under German rule (Gutman 62; Lewin 13). The size of the “Jewish quarter”—a term coined by the Nazis to recall other ethnic quarters within the city (as opposed to “ghetto”, a forbidden word)—was extremely small (Gutman 61). The population density of the ghetto was over 200,000 people per square mile; 30 percent of the population of Warsaw was condensed into an area that made up only 2.4 percent of the city (Gutman 60).

Both the boundaries of the ghetto and the number of people within it changed relatively frequently; the latter was caused by the relocation of Jews from smaller cities and towns to the Warsaw ghetto as well as the extraordinarily high death rate of its inhabitants due to disease and starvation (Gutman 63, 65). Rations consisted of only 184 calories a day, making food smuggling desirable, though it was as deadly as starvation for those who were caught (Lewin 21). In his memoirs, Jack Klajman, a young Jewish boy in Warsaw who considered himself one of the first food smugglers, described the effects of the mass starvation that ghetto residents faced: “By early 1941, it was common to see men, women, and especially children dying in the streets…When someone died, others stole the clothes off his or her body…Eventually, people became so blasé about death that no one even bothered to cover the bodies anymore” (17).

While the devastation of violence, overcrowding, starvation, and disease swept through the ghetto, its “residents” began to adapt as best they could, developing routines and falling into a relative rhythm of daily life as they adjusted to its new curfews and regulations. While many Jews participated in mundane factory work to produce goods for the Germans or were conscripted for forced labor, another sector of the population was engaged in illicit “underground” activity.

The “Underground”: Physical and Intellectual Resistance

From smuggling food and weapons to publishing illegal newspapers to coordinating acts of armed resistance, the various political and intellectual groups represented in this movement formed the core of the Jewish underground and played crucial roles in aiding the residents of the ghetto and in preserving its memory to the present day. The intellectual resistance that went into effect with the establishment of the Oneg Shabbat Archives and the physical resistance of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising provide two examples of unprecedented underground activity that changed the course of history.

The Oneg Shabbat (Shabbes) Archives was founded by Dr. Emmanuel Ringelblum, a Jewish historian, in October 1939 in order to preserve for posterity the true nature of events transpiring in the Warsaw ghetto (Kermish 4). Documents, surveys, monographs, letters, underground newspapers, newsletters, meeting agendas, diaries, and memos are a sampling of the writings contained in the Archive; material collected was often circulated among the political underground and cited in its bulletins and newspapers, and the stories that reached the free world often came from the Oneg Shabbat (Gutman 144). Ringelblum claimed in his diary on June 26, 1942, after an English radio broadcast cited an Oneg Shabbat report describing the conditions faced by Polish Jews: “The Oneg Shabbat group thus fulfilled a great historical mission, alerting the world to our fate…our pain and torment; our suffering and self-sacrifice under constant dread was not in vain. We have dealt a blow to the enemy. We disclosed his diabolic scheme to exterminate Polish Jewry which he had meant to execute quietly. We drew a line across his calculations and revealed his cards” (Kermish 34).

In September 1946 and December 1950, two of three parts of the Oneg Shabbat Archive were found buried in milk churns and tin chests within the confines of the former ghetto, largely due to the intercession of Hirsch Wasser, former secretary of the Archives (Lewin 13; Kermish 5). The subsequent publication of these documents has provided invaluable material for historians seeking to reconstruct Jewish perspectives, which were often harder to identify in comparison with the vast amount of official German documents produced during the same period.

While the Oneg Shabbat provided a means of intellectual resistance, the political groups whose newspapers it collected began to shape a course of physical resistance. This was a gradual and tedious process. Myriad political factions with diverse ideologies were represented in the Jewish underground, among them Zionists, Communists, and Revisionists (with many sub-groups stemming from them), and their differences in belief often caused tension when cooperation was of the utmost importance (Gutman 129). Nevertheless, these groups faced similar circumstances and shared the common dream of liberation for the Jewish people.

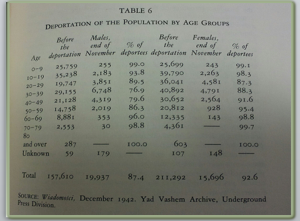

Deportation

On July 22, 1942, a proclamation was issued stating that all Jews (with few exceptions) were to be deported to the East, and that by 4:00pm of that same day 6000 Jews needed to be supplied; this was to be the minimum daily quota until the program was completed (Gutman 203). “Evacuation” to the East meant only one thing—arrival at Treblinka and imminent death. The deportation period from July 1942 – September 1942 (or Aktion) sent 253, 741 Jews to their end according to German statistics, though many Jewish writers claimed the number to be even greater; about seventy-five percent of the Warsaw ghetto’s population was annihilated, and children under the age of ten and adults over the age of sixty almost vanished from the ghetto (Gutman 211, 213, 270).

The fear and religious convictions that may have made many underground leaders cautious to retaliate were exacerbated by the fact that a course of action in response to the Aktion could not be immediately agreed upon. Taking matters into their own hands, representatives of three Jewish youth movements joined together to form the Jewish Fighting Organization, or Z.O.B. (its initials derive from its Polish name) on July 28, 1942 (Arens 111). The Z.O.B. began committing a series of arsons and several assassination attempts on members of the Jewish Police and the Judenrat, or Jewish council; started collecting a small stash of weapons; and published a manifesto in January 1943 as it anticipated a second round of deportations: “Not a single Jew should go to the railroad cars. Those who are unable to put up active resistance should resist passively, meaning go into hiding. Our slogan must be: ‘All are ready to die as human beings’” (Gutman 238, 240).

At the same time that the Z.O.B. was trying to instigate rebellion, another Jewish resistance group emerged—the Revisionist Jewish Military Union (known as Z.Z.W. because of its Polish initials) (Gutman 293). Its “ranks [were opened] to all those eager to fight the Germans, whether or not they were affiliated with any party or movement, especially if they already had acquired weapons of their own” (Arens 114). Fewer records exist regarding its inception and activities because all of its leaders were killed during the uprising, unlike the heads of the Z.O.B. (Arens 283).). Despite their common goal, “ideological differences of past years, completely irrelevant under present circumstances, prevented [the unification of the Z.O.B. and Z.Z.W.]”, and disagreements about how an armed resistance group should be structured also hindered the fusion of the two groups’ manpower (Arens 116).

Rebellion:

The fighters of the Z.O.B., inspired by the effectiveness of isolated incidences of force against the unsuspecting Nazis during the brief January deportation, began a campaign to increase its weapons arsenal and to mobilize fighters for the next German provocation. Vladka Meed, a Jewish woman who escaped to the “Aryan side” and served as a weapons courier for the Z.O.B., described the group as “consumed by excitement” after having received a shipment of fifty revolvers and fifty grenades from the Polish underground; they “spared no effort to obtain arms as soon as possible” (Meed 123). also began to assemble grenades, bombs, and Molotov cocktails, but it became clear that production on the intended scale meant that the chemical components purchased on the “Aryan side” needed to be smuggled into the ghetto, where they could be manufactured in “munitions” plants set up The ghetto was divided into zones, and Z.O.B. members made it their goal to “purge” the ghetto of Jewish collaborators, to raise funds for weapons, and to prepare for battle (Gutman, 340). The Z.Z.W. was also at work, and the tunnel that it dug from the ghetto to the Aryan side gave it access to trading with Polish underground groups and even resulted in its acquiring a machine gun and automatic weapons (Arens, 136). The regular Jewish population also began preparing for the next conflict—they built a network of underground bunkers complete with electricity, running water, and non-perishable foods (Gutman, 352 – 353).

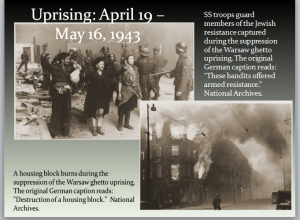

On the evening before Passover in 1943, the German troops moved outside of Warsaw to commence with the final liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto. By the early morning hours of April 19, the Germans had moved into the ghetto, and resistance fighters surprised them with an array of gunshots, Molotov cocktails, and homemade bombs. They also set off a land mine and set several German tanks on fire (Gutman 373 – 374). While the battle with the resistance fighters raged on in the streets, the Germans also encountered unexpected disobedience in the “battle of the bunkers” (Gutman 387). Afraid of what might be awaiting them underground, Nazi soldiers used police dogs, poison gas, and smoke bombs to drive non-combatant Jews from their bunkers. Eventually they resorted to burning or bombing the bunkers to ensure that civilians would not come out alive (Gutman 387).

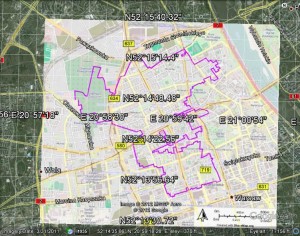

View Warsaw Ghetto in a larger map

The Germans initially set aside three days for the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, but the fighting raged for twenty-eight days, officially ending on May 16, 1943 (though sporadic fighting still broke out in the ghetto for several weeks afterward) with the bombing of the Jewish synagogue just outside the ghetto on the “Aryan side” (Kurzmann 344). The ghetto was razed shortly afterward.

Conclusion

While the Jews had not achieved a military victory—German statistics on May 16 accounted for 56, 065 Jewish casualties—they had certainly proven that they would not submit to the tyranny of Nazi Germany, and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, “more than any other event, symbolically ended two thousand years of Jewish submission to discrimination, oppression, and finally, genocide. It signaled the beginning of an iron militancy rooted in the will to survive, a militancy that was to be given form and direction by the creation of the state of Israel” (Kurzman 17). Little did the Nazis know that their plans to annihilate the Jews from the face of the Earth would backfire in such a way as to provide for the institution of an entire country for Jews, born from the ashes of their brave intellectual and physical resistance against the German program of terror.

Power Point: included in e-mail (includes commentary)

Preservation Path

Though this subject–the Warsaw ghetto uprising–is a sad one, it also imparts a message of hope. I enjoyed learning more about the ways in which the Jewish people of Warsaw refused to accept the tyranny of the Nazis and actively resisted them. A good deal of research went into creating the narrative and the graphic and visual representations; it’s a project I’d really like to preserve. I think the best method to use as a guide is the LOCKSS (“Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe!”) model; it involves saving digital media and files in separate formats and storing them in separate locations. The nature of the project itself has already been conducive to that; as I’ve created digital objects, like the map of the Warsaw ghetto overlaid on the map of modern Warsaw in Google Earth, I’ve both embedded the finished product in my blog and have also saved it as .jpeg files on my computer. I’ve saved the narrative text on a thumb drive, and I’ll planning to print out a hard copy of the entire thing for myself, as well. I can also e-mail it to myself and make a second copy of the completed project on a flash drive or on an external hard drive*. As the Library of Congress suggests, I should check these different media storage devices every few years to make sure they’re still compatible.

*This is what I hadn’t yet done–saved the entire blog post to a flash drive. Thankfully the nature of the project made it somewhat easy for me to recover my project from this morning because I had saved multiple pieces of it. Thank you so much for your understanding!

Works Cited

Arens, Moshe. Flags over the Warsaw Ghetto: The Untold Story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2011.

Gutman, Yisrael. The Jews of Warsaw, 1939 – 1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Kermish, Joseph, ed. To Live with Honor and Die with Honor! : Selected Documents from the Warsaw Ghetto Underground Archives “O.S.”. Jerusalem: Menachem Press, 1986.

Klajman, Jack. Out of the Ghetto. Edited by Antony Polonsky, Martin Gilbert, Aubey Newman, Raphael F. Scharf, and Ben Helfgott. Portland: Vallentine Mitchell, 2000.

Kurzman, Dan. The Bravest Battle: The 28 Days of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. New York: Da Capo Press, 1976.

Lewin, Abraham. A Cup of Tears: A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto. Edited by Antony Polonsky. Translated by Christopher Hutton. Padstow, England: T.J. Press Ltd., 1988.

Meed, Vladka. On Both Sides of the Wall: Memoirs from the Warsaw Ghetto. New York: Holocaust Library, 1993.